Lectures—I’ve had a few. I recall some as soporific, mechanically delivered verbal sludge. Others had me hanging on every word from a skilled communicator. Yet one lecture I recall most vividly, although delivered in a droning style, had me on the edge of my seat.

A group of theoretical physicists emerged in the early decades of the twentieth century, upending the settled world of classical physics. It included Einstein, Plank, Heisenberg, Schrodinger, Bohr… so many European names; and one notable British physicist, Paul Dirac. The legacy of this group is modern relativistic quantum physics, which underpins all of our modern electronics, including the astounding computing power of the smart phones we carry with us.

My sole personal encounter with one of this group, god-like figures to physics students of my generation, was at a lecture by Paul Dirac, 1933 Nobel Laureate and one-time occupant of Isaac Newton’s chair at Cambridge. In 1975 I was at a radio science conference at the University of New South Wales when news burst that Dirac was visiting the university and was about to give a public lecture. A group of us immediately abandoned the conference and headed for the advertised venue. It was well we rushed to get a seat: the tiered theatre soon filled far beyond its capacity of 400 or so, eager students sitting on every available step and a disappointed throng at the door turned away.

On cue, an apparently old and stooped man, shabby jacket over his jumper and a scarf wrapped around his neck in the British style, was ushered onto the platform of the theatre. He began to speak, quietly, almost diffidently, wandering the platform with eyes down and with little apparent awareness of his audience. We strained to hear, transfixed not by his delivery but by his presence. He spoke of debates with ‘Albert’ and the robustness of exchanges with other peers of that golden era of science, always using the first names of those giants of physics whose surnames litter the textbooks.

‘The field was so open in those days that even second-rate physicists could produce first-rate science,’ he noted in self-deprecation. ‘Today the field is so developed that first-rate physicists struggle to produce second-rate science.’

He would turn to the blackboard from time to time to outline a mathematical proof, his voice lost as he addressed the board. And then, abruptly, the lecture finished. He ceased his wanderings and stood impatiently as the local professor of physics gave an effusively tedious vote of thanks. Ignoring the ensuing enthusiastic applause, Dirac repositioned his scarf, shed mid-lecture in deference to the over-heated theatre, and headed for the door.

By any measure, the presentation style was abysmal. Yet what a memory the lecture leaves. The medium was most definitely not the message.

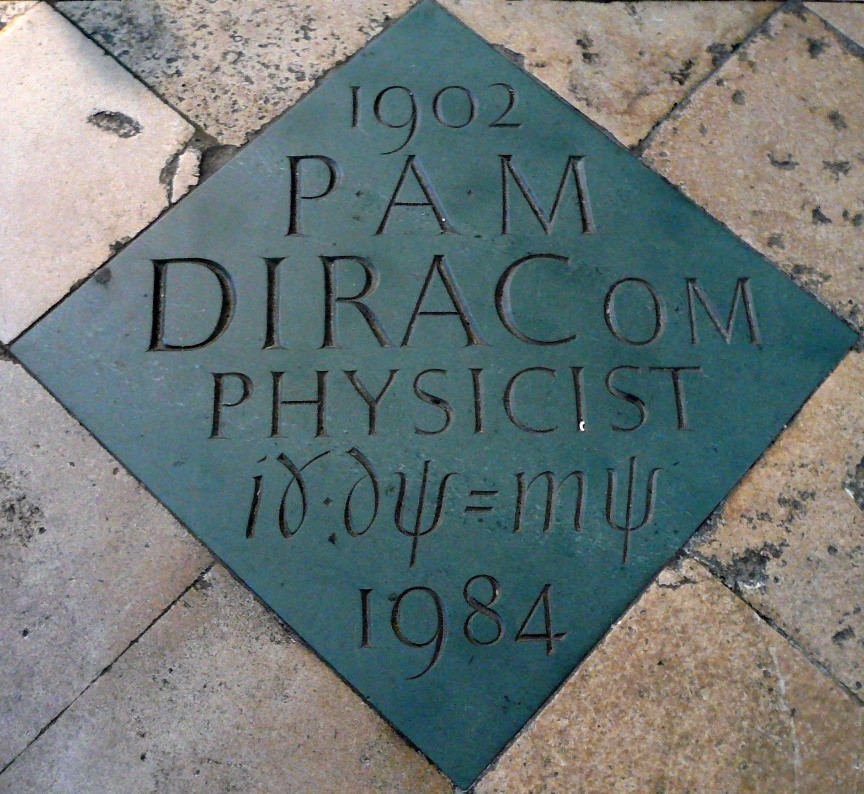

Postscript. Dirac, who was 73 when he visited Australia but appeared to me much older, died in 1984. In 1995 a memorial stone in his honour, showing his crowning achievement, the equation describing the inner workings of the electron, was laid in Westminster Abbey, where it touches the gravestone of Isaac Newton.

And a provocation for BWG poets: Dirac, the ultimate nerd, once said ‘The aim of science is to make difficult things understandable in a simpler way; the aim of poetry is to state simple things in an incomprehensible way. The two are incompatible.’